Dominating at Sea and on Land

The Triassic was the age of reptiles. Since the Early Triassic, several reptile clades have re-adapted from land back to the sea and diversified by occupying various ecological niches. Best known are the nothosaurs, some species of which reached up to five metres. With their long snouts with pointed teeth they were specialized fish and squid hunters. A broad skull with blunt teeth proves Simosaurus as a predator adapted to crush hard-shelled food. Even more specialized durophagous reptiles were the placodonts with their pronounced flat crushing dentition. The large pelagic ichthyosaurs went rarely astray into the Muschelkalk Sea. Hence, their bones are rarely found. Top predator of the hinterland was the high-walking terrestrial crocodile Batrachotomus, which is best known from Lower Keuper localities of the Hohenlohe country.

Long, pointed fangs with brownish enamel grooves are characteristic for Nothosaurus. Such teeth enabled Nothosaurus to seize its prey but not to shear it. Hence, nothosaurs had to swallow it in one piece. According to their prey, species of the genus Nothosaurus comprise different size classes between one and five metres, giving evidence of prey partitioning.

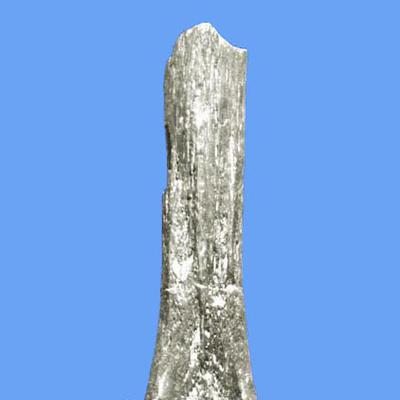

The twelve cervical vertebrae of the giraffe-neck reptile Tanystropheus were extremely elongated. The earliest finds of such bones were regarded limb bones and later interpreted as finger bones of flying reptiles. Only when articulated skeletons of Tanystropheus were discovered in black shales of Lombardy and Ticino, it became clear what the animal looked like. However, the life habit of this bizarre creature is still discussed. The photo shows a cervical vertebra of a juvenile individual.

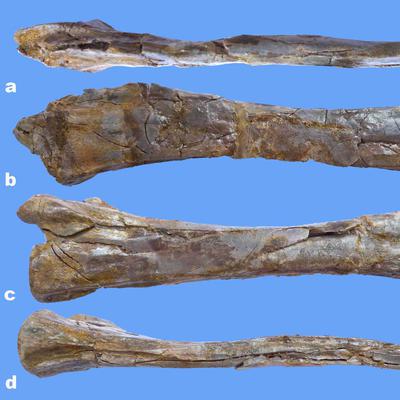

Batrachotomus kupferzellensis was the top predator in the hinterland of the Lettenkeuper swamps. Its long, dagger-like teeth with serrated edges enabled this rauisuchian land crocodile to attack much bigger animals and to slice them. Bones displaying biting traces of these deadly weapons give evidence that even the huge mastodonsaurs were preyed on.

Such osteoderms have long been assigned to the Aetosauria, which were widely distributed in the Late Triassic. Now it became evident that they belong to the Doswelliidae, an archosauriform family known from the Late Triassic of North America. The Lettenkeuper species was named Jaxtasuchus salomoni after River Jagst and in honour of the fossil collector Michael Salomon.

During the last years, excavating techniques in the Lower Keuper fossil site of Vellberg were refined and yielded a plethora of small reptile bones. By this, understanding the biota of the Middle Triassic Lettenkeuper lakes and swamps with their diverse faunas and floras was much improved. Among the latest discoveries are tiny jaws with teeth grown together with the bone. These finds allowed dating back the presence of rhynchocephalian reptiles to Ladinian times.

The discovery of skull and postcranial bones of the ancestral turtle Pappochelys rosinae in the Lettenkeuper of the Schumann quarry caused a sensation in the scientific world a few years ago. These finds proved the turtles to be rooted among diapsid reptiles (with two temporal openings) and enlightened the origin of the turtle armature. However, Pappochelys, does not look like a real turtle, but rather like many other reptiles. The photo shows a dentary assignable to Pappochelys.