Accummulations of bones, teeth, and scales in countless ‘bone beds‘ provide evidence of the highly diverse fish faunas in the Muschelkalk Sea and the Lower Keuper waters. However, not every species was described from articulated skeletons, but rather from isolated bones, teeth, or scales, which are intermingled in the bone beds as a puzzle with many parts lacking. Among the cartilaginous fishes (Elasmobranchia), the hybodont sharks with either multicuspid or flat crushing teeth for hard food dominate. The most diverse group are the ray-finned Actinopterygia with the primitive Palaeopterygia, most of which have thick ganoid scales forming a flexible external skeleton. The lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygia) are represented by lungfish and coelacanths.

Many primitive sharks bear a bony spine at the anterior side of their dorsal fins, which is deeply inserted in the body. Hybodontid fin spines are characterized by a longitudinal striation and a double series of teeth along the posterior side. It is still uncertain to which teeth the 30 cm long figured spine belongs, because spines and teeth have not yet been found together. However, there is some evidence that it belongs to Acrodus gaillardoti.

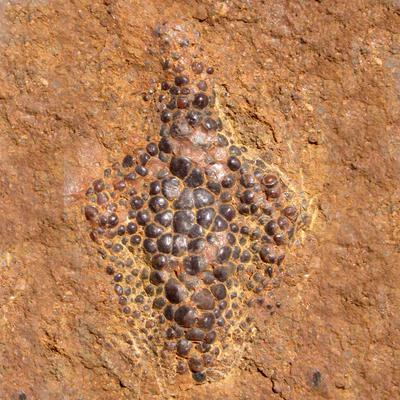

Depending on their position within the jaws, the multicuspid Parhybodus teeth are different. They were previously described as separate species, e.g. teeth with one long central tip as Parhybodus longiconus. Nowadays they are comprised as Parhybodus plicatilis. The upper specimen from the Muschelkalk-Keuper boundary bone bed has an abraded tip.

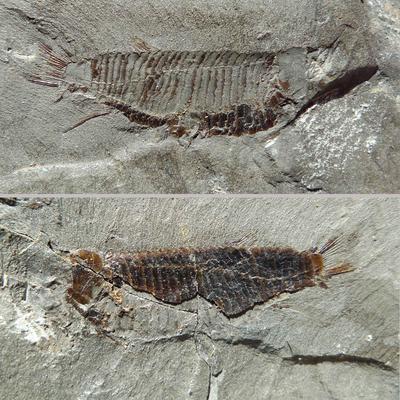

The Lettenkeuper brackish lakes were inhabited by highly diverse fish faunas, but articulated skeletons are rarely found. The picture shows the small Habroichthys, which is only a few centimeters long. Complete individuals of this genus are best known from the Tethyan Middle Triassic of the Alps and South China.

During the last years, tooth batteries devoid of a bone base from the boundary bone bed have been assigned to the high-bodied actinopterygian Bobasatrania, which is well known from the Early Triassic of Greenland and Madagascar. The Muschelkalk tooth plates can now be confidently assigned to this genus as Bobasatrania scutata.

Serrolepis suevicus is another small actinopterygian fish (Polzbergiidae) which is commonly found in some Southwest German Lower Keuper beds. However, really abundant are only its high scales, which are strongly serrated at their posterior margins. The skeleton in the picture shows the differentiated squamation and the jaws with long pivot teeth.

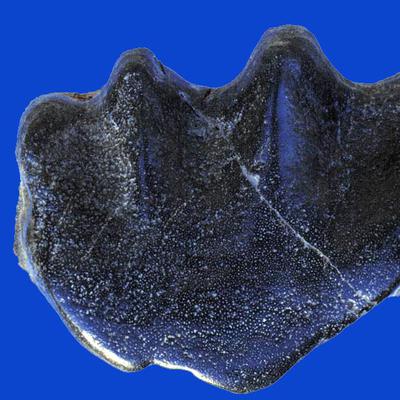

The Lower Keuper yielded two genera of lungfish (Ceratodontidae). In the bone beds, their black comb-like tooth plates are found, but they are not common. Even rarer are the fragile scales and bones of the skull roof. The large tooth plate figured from the Crailsheim boundary bone bed is of an approx. 2 m long Ceratodus kaupi.

The Muschelkalk Sea and the Lettenkeuper brackish lakes and deltaic rivers were also inhabited by several coelacanth genera. The Muschelkalk has even yielded complete skeletons preserved in limestone nodules. The picture shows the pterygoid bone of the skull of a not yet described Lettenkeuper coelacanth.

Bone beds are generally defined as sediment bodies containing abundant vertebrate remains. The English term bone bed was adopted into the German geological terminology. However, ‘Bonebed‘ is here used in a restricted sense as a condensed layer of bones, teeth, and scales accumulated through long periods of time. By continuous reworking, the resilient material was increasingly abraded and condensed, but bones and particularly enamel are of high fossil potential. The best known ‘Bonebed‘ is a decimetre-thick dark grey or rust-coloured layer famous for its vertebrate fossils. It separates the Muschelkalk from the Keuper in vast parts of South Germany.